How London became Suffragette City

By the start of the 20th century, large numbers of men had won the right to vote while women seethed on the sidelines. Then the Suffragettes, members of the Women’s Social and Political Union, set London alight with a revolutionary style of direct action. By Jane Hayward

Cartoon, Millar and Lang Co Ltd; Sylvia Pankhurst photo on home page, Spaarnestad Photo via Nationaal Archief. Both via Wikimedia Commons

-

The long wait for change

In the 1890s, Emmeline Pankhurst felt the same way as many suffragists and social reformers who had argued for decades that women, like men, deserved the right to vote in political elections: frustrated and angry. Since changes in law typically emerged from private persuasion among the wealthy and privileged classes, she and her like-minded husband Richard, a barrister and businessman, had hosted endless gatherings at both their Manchester and London homes. (The latter, at 8 Russell Square, is now the site of the Kimpton Fitzroy London Hotel.) Labour Party leader Keir Hardie was a regular attendee. Yet despite endless strategising, the stark reality was that no Government action ever resulted. This glacial pace of change set the stage for the emergence of the Suffragettes as Mrs Pankhurst’s fury projected her to a central role in British women’s history.

Emmeline Pankhurst in the 1880s, LSE Library via Wikimedia Commons

-

London becomes the battlefield

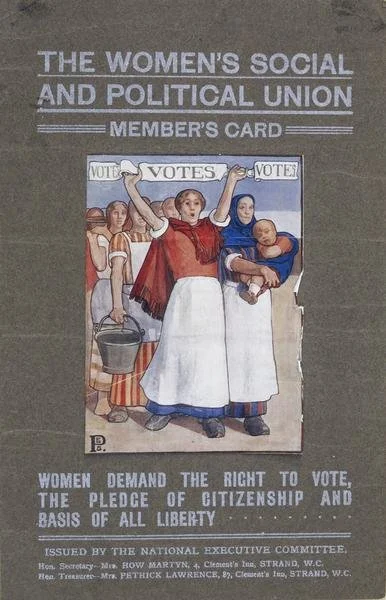

Richard’s death in 1898 was a turning point for Mrs Pankhurst. It freed her from conventional political life and allowed her to take an extraordinary decision: she would confront the Government using direct action. “Deeds not words” became her motto and the central tenet of the Women’s Social and Political Union, which she founded in 1903, aged 45. In 1906 she moved to London full-time in order to be close to power. Money was now tight, so she set up an HQ at 4 Clement’s Inn, in the apartment of her allies and key financiers Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence. (The London School of Economics now stands on the site.) Mrs Pethick-Lawrence became the WSPU’s treasurer, and the couple were generous in supplying accommodation. Joining Mrs Pankhurst in the capital and the fight - albeit in very different ways - were her three remarkable daughters, Christabel, Sylvia and Adela.

WSPU meeting c1906, Mrs Pankhurst on far right, LSE Library via Wikimedia Commons

-

Sylvia: the art of protest

Sylvia, the middle Pankhurst daughter, was a gifted artist who was already living in London, having studied at the Royal College of Art in Kensington from 1904 until 1906. Her rented home at elegant 120 Cheyne Walk in Chelsea had become a base for the WSPU, where she’d design inspirational banners and posters in a style influenced by pre-Raphaelites as well as social realism. She wasn’t elitist, however: an earlier tour of England’s factories and mills where she painted working women marked her out as a very different personality to early stereotypes of suffragists as genteel activists. As the Suffragette campaign began, she sacrificed her art to become a full-time activist.

WSPU membership card art by Sylvia Pankhurst: London Museum

-

Christabel sparks the term 'suffragette'

Mrs Pankhurst’s oldest daughter Christabel was her closest ally. A law graduate who was both charismatic and persuasive, she inspired near-religious adoration within the WSPU where her role was organising secretary. “Do not beg, do not grovel,” she told its 2,000 members. Instead, she strategised a series of confrontations and aggressions in 1906, which led the Daily Mail to coin the term Suffragettes for her followers at the WSPU. Christabel decided to target middle- and upper-class women, arguing that they would attract the best publicity and subsequently work to improve other women’s lives.

Photo: LSE Library via Wikimedia Commons

-

A working-class rebel joins the team

An authentic working class voice was invaluable to an organisation that was often accused of being for the upper ranks only. And so it proved with 26-year-old Annie Kenney (above, with Christabel Pankhurst), who had lost a finger as a child worker in an Oldham mill. Having become involved with the Pankhursts in Manchester, she quickly proved fearless in activism, with a devotion to Christabel Pankhurst that would shape her work. Her brief in 1906 was “to rouse London”. She was paid £2 a week - twice the wage of a skilled (male) manual worker - to set up the WSPU’s first branch at 105 Barking Road, Canning Town. An articulate, convincing speaker, Annie wasn't too proud to don clogs and shawl to wordlessly send the message that working-class women supported the call for the vote.

Photo of Anne and Christabel, Wikimedia Commons

-

The fight begins

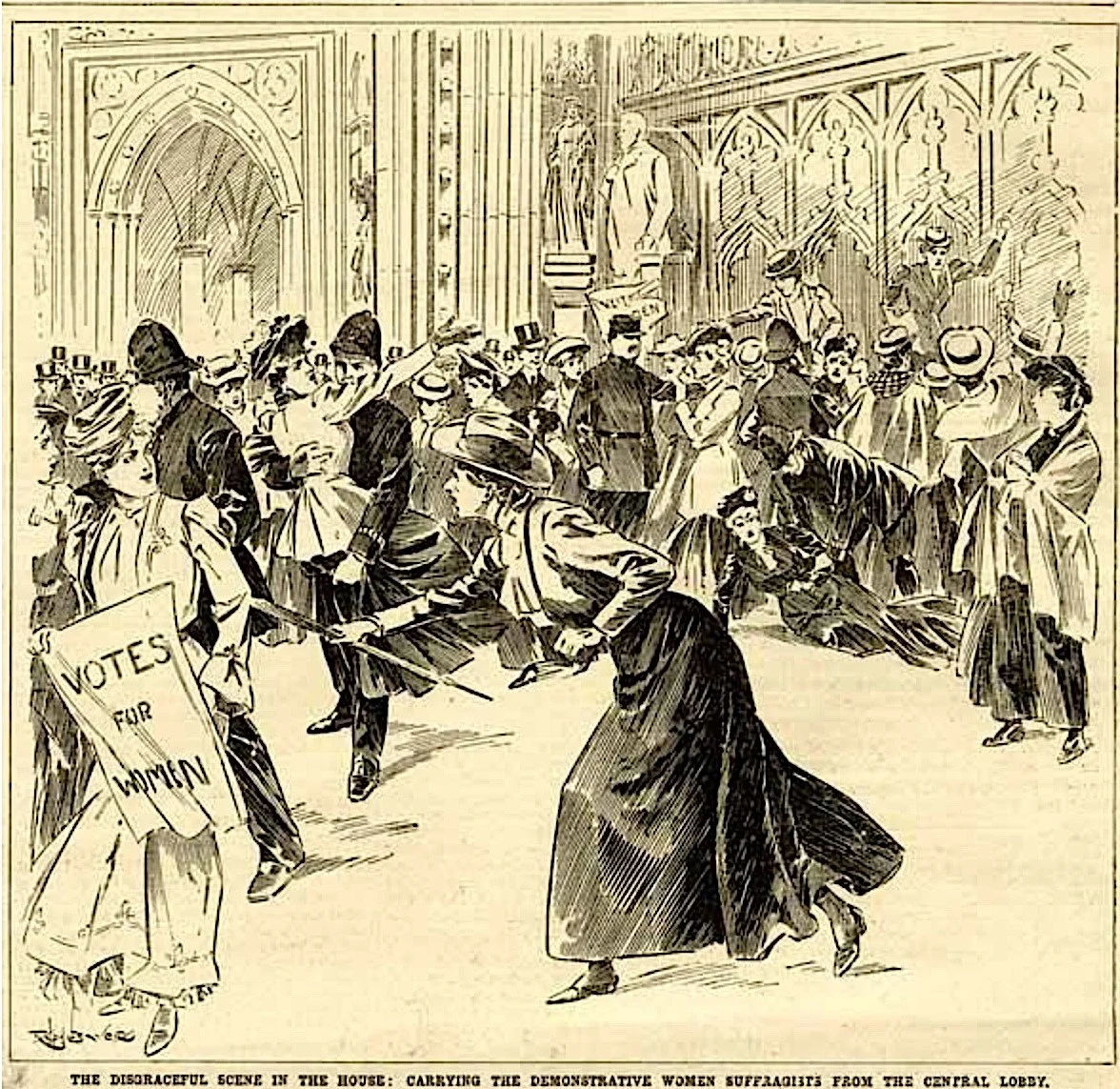

The campaign of direct action in London began in 1906. Mrs Pankhurst was determined to show that women were at last ready to “fight for themselves…for their own human rights”. On 19 February she led the WSPU on a groundbreaking march to "the heart of power”. Up to 400 women from all backgrounds walked together from St James’ Park tube station to Caxton Hall in Westminster to mark the State Opening of Parliament - a clear declaration of intent. “Smiling but earnest,” was the description of the marchers in the Daily Mirror the following day. A whirlwind of activity followed with protests at 10 Downing Street and the House of Commons and the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s home. The authorities responded with arrests. Teresa Billington, a 29-year-old schoolteacher from Lancashire, became the first suffragette to be sent to Holloway Women’s Prison in North London; she received two months for assaulting a policeman but was released against her will when a well-wisher paid her fine.

Illustration of 1906 House of Commons invasion, Daily Graphic via Wikimedia Commons

-

The first 'mass demo'

Taking part in a demonstration was unthinkable to most ‘respectable’ women. The risks to their reputation and livelihood were too dreadful. This changed in February 1907, when more than 3,000 suffragists - an unprecedented number - from different societies came together for The United Procession of Women. Their aim was to pressure the Liberal Government to honour its promise to introduce a bill for women’s voting rights. As torrential rain fell, a brass band led the women - some aristocrats, many workers carrying trade banners, all wearing floral rosettes - from Hyde Park to the Strand. “Mud, mud, mud,” was how the march’s leader Millicent Fawcett, a staunch advocate of peaceful campaigning, described the day, which became known as The Mud March. But despite a lack of government response, the long-range forecast was far from gloomy. Onlookers’ reactions had been mostly positive. Ditto the press coverage. And women found the courage to show their conviction in public. The WSPU had refused to attend officially, but many of the leaders came individually and took on board the powerful impact of a colourful, unified spectacle - something they would adapt and use with spectacular success.

Photo of the Mud March, Daily Mirror via Wikimedia Commons

-

Learning to create headlines

From Autumn 1907, sole female figures began to spring up outside London landmarks like The Oval cricket ground and Hampton Court Palace. These were volunteers selling the WSPU’s new newspaper Votes for Women. Shouting the title was an act of defiance in itself, and the women frequently found themselves moved from the pavement into the gutter by the police and on the receiving end of abuse by passers-by. The newspaper, financed and edited by Emmeline and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence and printed by members at the society’s HQ, proved highly effective at getting out the WSPU’s message. It shifted from monthly to weekly publication and reached a peak circulation of 33,000 in 1909.

Photo: Charles Chusseau-Flaviens via Wikimedia Commons

-

Developing the brand

Green for hope, white for purity, and purple (or violet) for “the royal blood that flows in the veins of every Suffragette”: these were the colours chosen for the campaign by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence in 1908. (The initial letters ‘g’, ‘w’ and ‘v’ cleverly created an acronym for Give Women Votes.) Drawing inspiration from the Mud March, the WSPU’s strategy was to dress in fashionable, feminine styles to counter the ugly, masculine stereotypes hurled at suffragettes, and show them off in processions on the streets of London. As the idea caught on, Selfridges and Liberty sold ribbon, accessories and ‘secret’ pieces such as embroidered stockings in suffragette colours. Jewellers Mappin & Webb too created special tricolour designs. The widespread adoption of ‘Suffragette style’ meant the women’s message was not only heard but seen (and, crucially, admired) all across the capital

Rosette: property of LSE Library

Women are “awake at last. [On their first march on Parliament] they were prepared to do something that women had never done before—fight for themselves. Women had always fought for men, and for their children. Now they were ready to fight for their own human rights. Our militant movement was established.” Emmeline Pankhurst